March 16, 2020 | Nature Sustainability | Source |

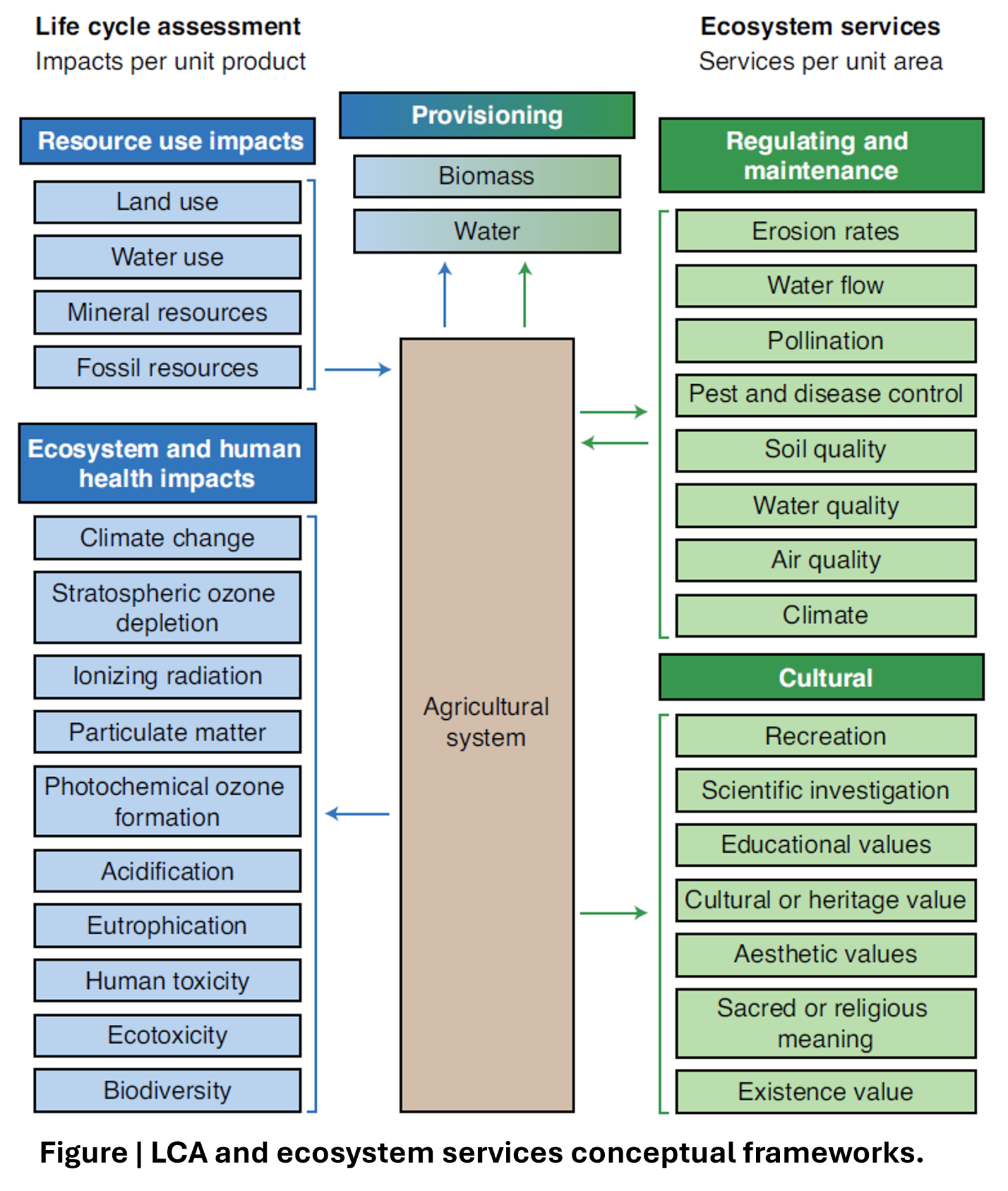

Introduction: Researchers from INRAE (France), Aarhus University (Denmark), and Chalmers University of Technology (Sweden) argue that conventional Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) misrepresents organic and other agroecological systems, highlighting the need to strengthen LCA to guide food-system transformations toward the SDGs and Paris Agreement. They point to 3 core gaps: missing indicators for key environmental issues, a narrow product-based perspective, and inconsistent treatment of indirect effects. To address these, the article contrasts LCA with the ecosystem-services framework and outlines pathways to make assessments more aligned with sustainability transitions.

Key findings: The article shows that LCA systematically favors high-input systems by minimizing impacts per kilogram while overlooking ecosystem services at the landscape scale. Despite rapid growth of agri-food LCAs, essential dimensions of agroecological performance remain poorly represented. Organic systems demonstrably enhance biodiversity (~30% higher species richness) and soil microbial activity, yet biodiversity is considered in fewer than 5% of livestock LCAs and in only 12% of organic–conventional comparisons. Soil health contributions from diverse rotations and cover crops are also neglected, with some models even treating soil as part of the “technosphere,” excluding toxicity effects. Pesticide impacts are similarly underestimated: while global use rose from 1.5 to 2.6 kilograms of active ingredient per hectare between 1990 and 2015, ecotoxicity appears in only 14% of livestock LCAs and toxicity in 26% of organic–conventional studies.

In addition, current LCAs rarely account for nutritional quality, product attributes, or ethics such as animal welfare, and assigning extra GHGs to organic systems through Indirect Land-Use Change (ILUC) or “carbon opportunity cost” oversimplifies complex land-use dynamics. The authors recommend strengthening LCA with new indicators for soil degradation, biodiversity, and pesticide impacts; combining product- and area-based units; integrating ecosystem-service valuation; regionalizing data; and treating indirect effects with caution to provide more balanced guidance for agroecological transitions and SDG-aligned policy.